Closing connections gracefully is an old and new problem in network programming. In the HTTP/1.1 days, this did not get attention since HTTP/1.1 is a synchronous protocol. However, as Niklas Hambüchen concretely and completely explained, HTTP/2 servers should close connections gracefully. This is because HTTP/2 is an asynchronous protocol.

Unfortunately, most HTTP/2 server implementations do not close connections gracefully, hence browsers cannot display pages correctly in some situations. The first half of this article explains the problem and its solution step by step in general. The second half talks about how to implement graceful-close in Haskell network library.

Normal cases of HTTP/1.1

Roughly speaking, synchronous HTTP/1.1 can be implemented as follows:

- Browser: the loop of writing request and reading response

- Server: the loop of reading request and writing response

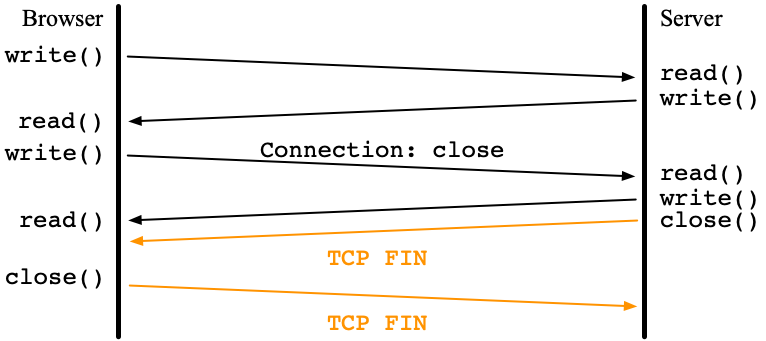

Since HTTP/1.1 uses persistent connections by default, a browser should set the Connection: close header to close the current connection.

When the server received the Connection: close header,

it closes the connection by close() after sending its response.

Of course, the browser knows that the connection is being closed.

So, the browser reads the response until read() returns 0,

which means EOF.

Then, the browser closes the connection by close().

Error cases of HTTP/1.1

For security reasons, HTTP/1.1 servers close connections. The followings are typical situations:

- Idle timer is expired

- The number of requests reaches the limitation

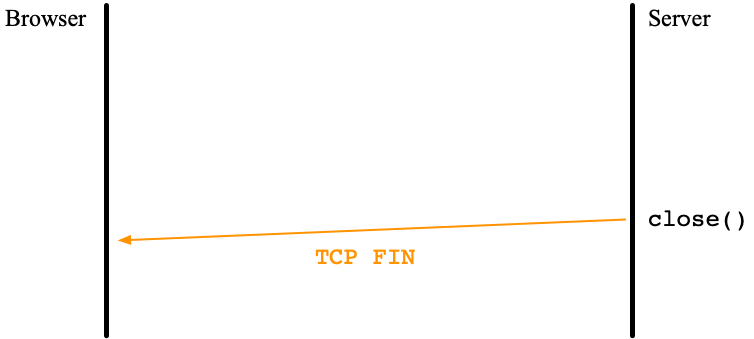

In these cases, an HTTP/1.1. server calls close() resulting in generating TCP FIN.

When the browser tries to write the next request to the same connection, it would be nice to see if the connection is alive. Are there any system calls to check it? If my understanding is correct, there is no such system calls without IO. What the browser can do is just read or write the connection optimistically if it wants to reuse the connection.

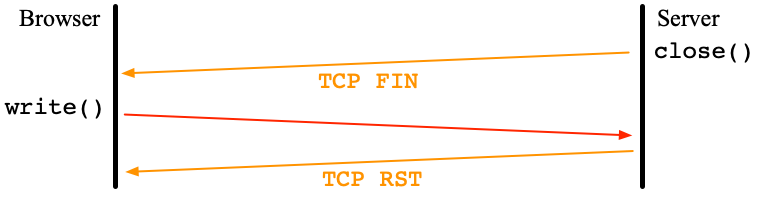

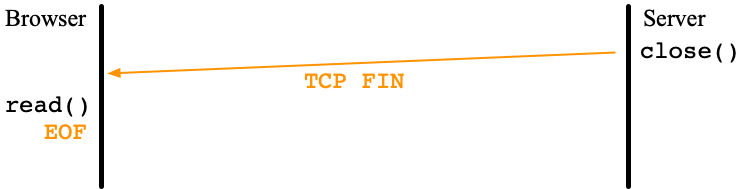

The case of TCP FIN

So, what happens if the browser reads or writes the connection which has already received TCP FIN?

write() succeeds. However,since the server socket is already closed, the TCP layer of the browser received TCP FIN, which is not informed to the browser.

read() return 0, EOF, of course.

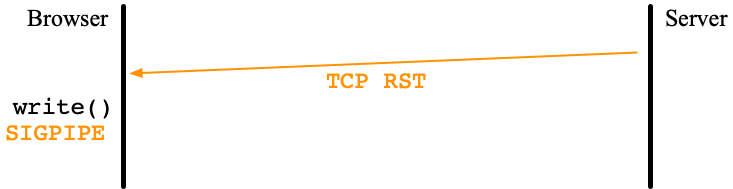

The case of TCP RST

Another intersecting question is what happens if the browser reads or writes the connection which has already received TCP RST?

write() causes SIGPIPE. If its signal handler ignores it, write() is resumed and returns EPIPE.

read() returns ECONNREST.

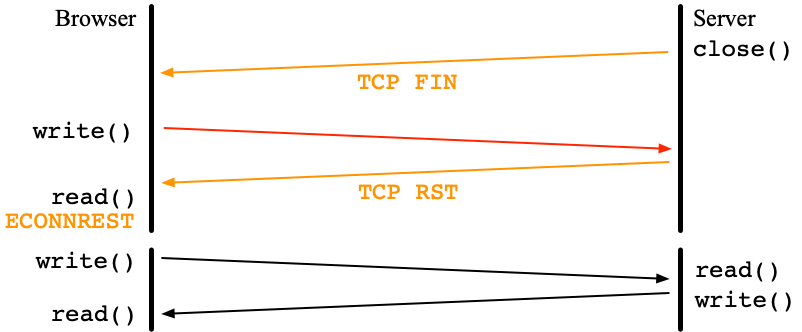

Recovering in HTTP/1.1

Suppose that an HTTP/1.1 server closed a connection by close() but

the browser tries to send one more request.

When the TCP layer of the server received the request,

it sends TCP RST back to the browser.

The browser tries to read the corresponding response and notices that

the server resets the connection.

So, the browser can make another new connection and re-send the request to the server.

In this way, recovering in HTTP/1.1 is not so difficult.

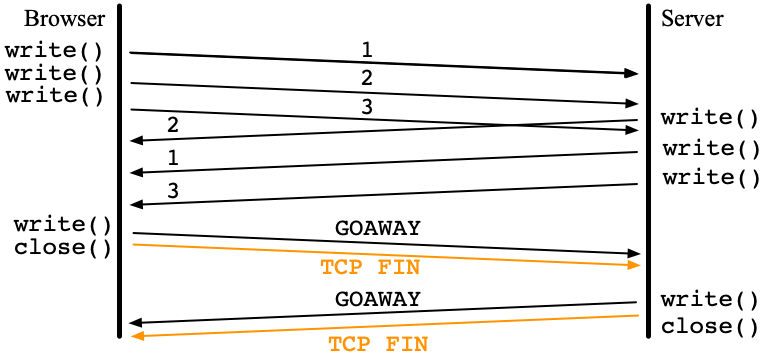

Normal cases of HTTP/2

HTTP/2 uses only one TCP connection between a browser and a server. Since HTTP/2 is asynchronous, the browser can send requests at anytime. The server can send back responses in any order. To combine a request and its corresponding response, a unique stream ID is given to the pair. In the following figure, the order of response 1 and response 2 is flipped.

To close the connection, the browser should send GOAWAY.

When the HTTP/2 server received GOAWAY,

the server should send back GOAWAY.

Typical implementations call close() after that.

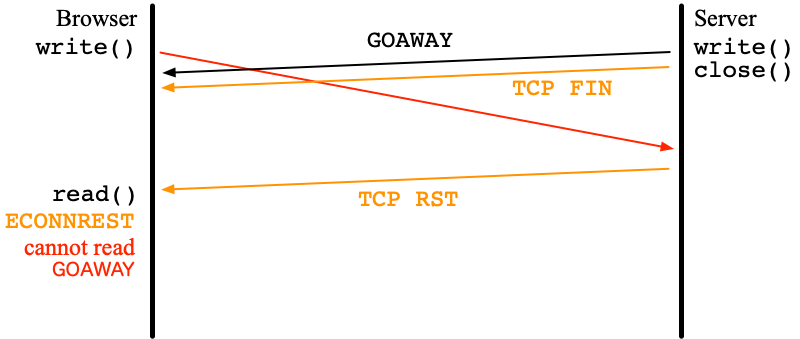

Error cases of HTTP/2

For security reasons, an HTTP/2 server itself closes a connection

by sending GOAWAY.

Again, typical implementations call close() after that.

It is likely that the browser sent a request asynchronously and the request reaches to the server after the socket is gone. In this case, as explained earlier, TCP RST is sent back to the browser.

Unfortunately, the TCP RST drops all data to be read in the TCP layer of

the browser.

This means that when the browser tries to read its response,

only ECONNREST is returned.

GOAWAY disappears.

GOAWAY contains the last stream ID which the server actually processed.

Without receiving GOAWAY, the browser cannot tell the recovering point.

In other words, the browser cannot render the target page correctly.

This problem actually happens in the real world.

And most HTTP/2 server implementations have this problem.

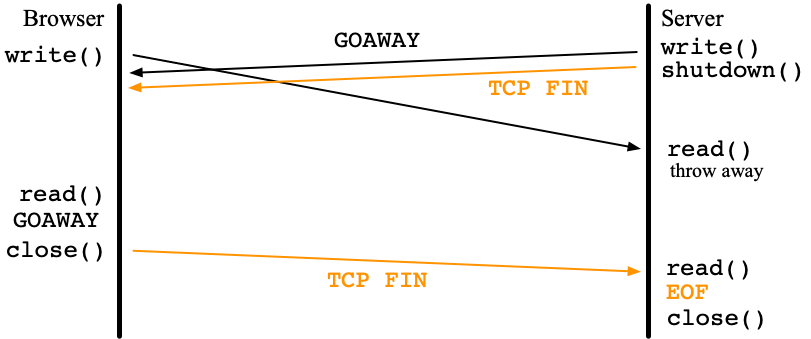

Graceful close

So, what is a solution? The masterpiece book, "UNIX Network Programming Volume 1: The Sockets Networking API (3rd Edition)", W. Richard Stevens et al. suggests the following way.

- The server should call

shutdown(SHUT_WR)to close the sending side but keep the receiving side open. Even if requests reach to the server aftershutdown(), TCP RST is not generated. - The browser can read

GOAWAYin this scenario and send backGOAWAYfollowed byclose(). - The server should read data until

read()returns 0, EOF. - The server finally should call

close()to deallocate the socket resource.

It is not guaranteed that the browser sends back TCP FIN.

So, the server should set time out to read().

One approach is the SO_RCVTIMEO socket option.

Implementations in Haskell

From here, I would like to explain how to implement graceful-close in Haskell network library.

Approach 1: the SO_RCVTIMEO socket option

After reading "UNIX Network Programming", I started with the C-language way but many features are missing in the network library.

- To time out reading,

SO_RCVTIMEOshould be supported insetSocketOption. - Since

SO_RCVTIMEOis effective only for blocking sockets, a function to set a non-blocking socket back to blocking is necessary. - Receiving data from blocking sockets without triggering the IO manager is also needed.

I confirmed that this actually works but threw this away. To not block RTS by calling the receiving function of 3, the function should be called via safe FFI. This means that an additional native (OS) thread is consumed. Closing connections should not be that costly. All in all, blocking sockets are not the Haskell way!

Approach 2: the timeout function

Of course, a very easy way is combine the timeout function and the original recv function which may trigger the IO manager.

This actually works.

But again I threw this away since an additional lightweight thread is consumed in timeout.

Approach 3: the threadDelay function

I finally hit upon the idea of threadDelay.

For this approach, a new receiving function is necessary.

It uses non-blocking socket and does not trigger the IO manager.

The algorithm is as follows:

- loop until the time out is expired

- reading data

- if it returns EAGAIN, call

threadDelaywith a small delay value. If it returns data, breaks the loop.

The advantage of this approach is availability. This works on all platforms with both threaded and non-threaded RTS. The disadvantage is that the timing of timeout would be inaccurate.

Approach 4: callbacks of the IO/Timer manager

Michael Snoyman suggested to use a pair of callbacks for the IO and Timer managers.

First, an MVar is prepared.

Then the main code sets a callback to the IO manager asking to put data

to the MVar when available.

At the same time, the main code also sets a callback to the Timer manager asking to put a time-out signal to the MVar when the timeout is expired.

The two callbacks race and the main code will accept the result of the race through the MVar.

This idea is awesome because no resource is wasted. What I was impressed is that he knows the IO/Timer managers better than me, who is one of the developers of the mangers!

Final remark

The Haskell network library version 3.1.1.0 will provide gracefulClose.

For threaded-RTS on UNIX where the IO manager is available, approach 4 is taken.

For Windows or non-threaded-RTS where the IO manager is not available, approach 3 is taken.

EDIT: It appeared that approach 4 leaks TCP connections. So, the current network library adopts approach 3 on all platforms.

My deep thank goes to Niklas Hambüchen for pointing out this problem, discussing solutions patiently and reviewing my implementations thoroughly. I would like to thank Tamar Christina for helping the development on Windows and Michael Snoyman for suggesting approach 4.